Acrostics: Pictured in rhyme & colour

Published by Artists' Choice Books (2003)

Introduction

An acrostic (from the Greek akros, end, and stichos, a line of verse) is nowadays most commonly defined as a type of puzzle, often in verse form, in which certain letters (usually the first) of each line spell out a word.

The origins of the genre are disputed, but ancient. The Sybilline Prophecies are in acrostic verse. The famous SATOR square, discovered in the ruins of Pompeii, is an elegant and intriguing combination of acrostic, word square and palindrome, commonly interpreted as a sign whereby persecuted Christians might recognise one another. The Bible, too, contains a number of acrostics, and a predilection for the genre endured within Christian literature until about 700 ad.

From then on, secular acrostics have appeared with greater or lesser regularity throughout Europe - enjoying a revival under Elizabeth 1st in whose honour Sir John Davies wrote his Hymns to Astrea - often as love tokens, or poems of praise. Shakespeare used them, as did John Salusbury, to whom Shakespeare's Phoenix and the Turtle is dedicated.

It was during the 19th century, however, that the genre enjoyed its greatest spell of popularity. In 1846 Edgar Allen Poe wrote a Valentine poem which spelt out the name of Frances Sargent Osgood in the first letter of the first line, the second letter of the second line, and so on. Queen Victoria was particularly fond of the double acrostic, which she helped to popularise. And of course, Lewis Carroll was fascinated by word games and patterns, and dedicated numerous acrostic poems to his young friends, notably his affectionate poem Little Maidens, when you look . . ., which contains the names of Alice, Lorina and Edith Liddell. Later, Edward Lear and Mervyn Peake both toyed with acrostic and pattern poetry, as did Edward Corey, and it is perhaps this association with children's literature and nonsense rhyme, along with that of the sentimental 'love-knot' pattern poems of the Victorian era, that has contributed to its dwindling popularity over the past half century.

What is it, then, about the acrostic form that continues to challenge and engage? In the light of its history I believe it would be wrong just to dismiss it - as some critics have - as a fad or a game. Acrostic verse goes much further than a lover's conceit, a letter-code or a childish puzzle. A good acrostic is made up of the haiku-like combinations of simplicity and precision, a playfulness merged with deeper, almost occult undertones, a childish delight in the shapes and sounds of words coloured with a subtle and adult appreciation. It has a diversity of voices; it can sing praise, sigh with love, or slyly satirise an enemy. It may encrypt its message or trumpet it aloud, all with a wink and a secret smile to the reader.

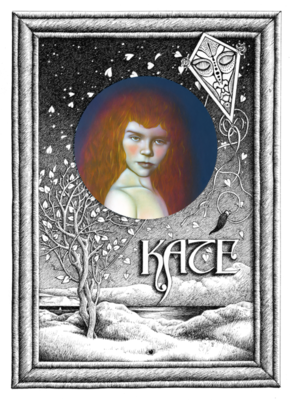

For me, it is with Lewis Carroll - and his natural successor, Graham Ovenden - that acrostic verse has the most resonance and style. Both are artists who combine a strong

visual aesthetic with a deceptive, childlike simplicity. Both are unashamedly eccentric, taking pleasure in the whimsical and the grotesque. Both are chroniclers of the photographic image, with a particular sensitivity to the transience of youth and beauty. Both have a special, almost pagan reverence for children and Nature. Both share a deep nostalgia for a golden past that has never quite existed beyond the mystic state of grace represented by childhood.

I have been an admirer of Graham Ovenden for nearly twenty years, although we only met face-to-face in 2002, when I contacted him to commission a portrait of my daughter, Anouchka. Arriving (rather nervously) at Graham's home, the legendary Barley Splatt, on a glorious summer's day, my husband, my daughter and I were greeted by a serene and genial gentleman with a mischievous smile who immediately invited us to join him for a walk up the river. We accepted, little suspecting that up the river meant precisely that; a mile-long walk along the bed of a clear and fast-moving little river, while Graham, in boots, gaiters and floppy hat, glided ahead of us, impervious to rocks, brambles or the occasional stretches of deep water which soaked him to the waist. We took off our shoes and joined him; my daughter with the immediate, unquestioning glee of a puppy off the leash, my husband and I with a hesitancy that quickly - and rather to our surprise - turned to pleasure. I suspect it was a test; a means of determining if we had the spirit, the humour and the joie-de-vivre to cherish a work of art by Graham Ovenden. I suppose we passed; in any case, a few days later he presented us with an acrostic poem dedicated to our daughter, with a handwritten postscript, river-walking will never be the same again.

This small episode, to me, sums up the artist perfectly. As with Lewis Carroll, there is something of the holy fool about Graham Ovenden. He is wholly, effortlessly erudite, and yet he takes delight in the simplest of things. His art is subtle and ambiguous; and yet he refers to his drawings as 'scribbles' and exhibits childrens' paintings in his studio. He lives life in the manner of a great adventure, and has a contagious and irrepressible enthusiasm for those things that make life worth living. Acrostic verse seems a perfect vehicle for this state of being. Even at its most passionate, there is an inherent playfulness about the genre, a refusal to take itself entirely seriously. This, too, is part of the appeal of Graham Ovenden. He may lead you down unexpected paths, but they are always paths worth travelling. I hope you enjoy this book as much as I do.

Joanne Harris, July 2003